Elizabethan Ships and Merchants Associated with Tewkesbury

Peter Raggatt was born in 1940 in Tewkesbury, a member of the Raggatt family of artisan engineers. Educated at Tewkesbury Grammar School, he subsequently studied at Oxford University (Chemistry and then research for a D.Phil. in Biochemistry). His career took him to the Medical School labs in Universities (Glasgow, Harvard, London and Cambridge) on the application of biochemical tests in medical diagnosis and in research into human disease, especially endocrinology. In 1968 he married Eileen Dickie, has four grown-up children and six grandsons. Now retired, he lives in St. Neots, Cambridgeshire, and is interested in local history and in how to communicate it. He is a member of THS.

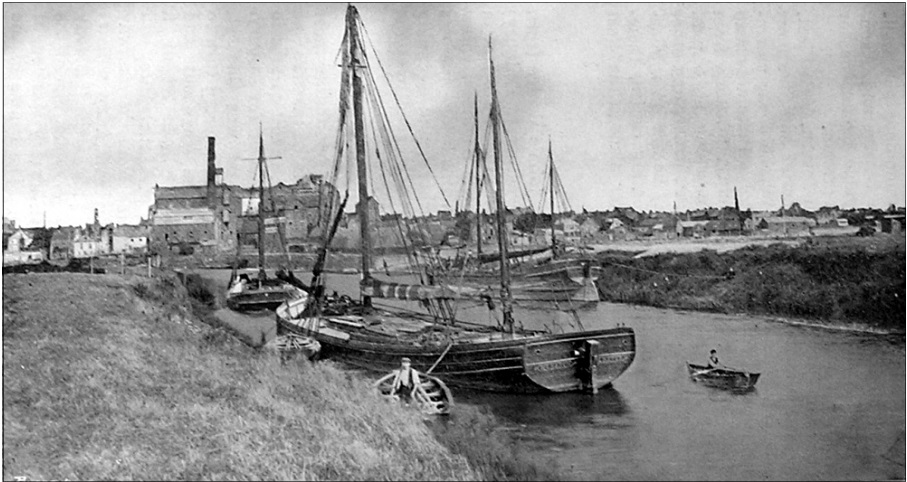

The older ones among us can remember the grain barges coming up the Severn to Healing’s Mill: long, narrow, rather grubby barges, powered by unromantic diesel engines. The Severn ‘trows’ (sailing barges) are much more romantic and something can be found about them and the trading traffic on the Severn in the 18th and 19th centuries on the internet (often un-referenced data). The Severn sailing trow ‘Spry’ has been restored and preserved at Blists Hill Museum, Ironbridge (2014). Clearly, however, trade followed the Severn in earlier centuries also.

Recently I came across a book by accident in the library of a house in Devon. The title of the book suggested it might be rather obscure: The Welsh Port Books (1550-1603) with an analysis of the customs revenue accounts of Wales for the same period. 1 I pulled it from the shelf, glanced at the index and, to my surprise, I found several mentions of Tewkesbury. The book was written by Edward Arthur Lewis in 1927 and it is still available in the Bodleian Library and a few others have survived; but it was never a popular book!

In 1913 Dr. Edward A. Lewis, an academic of Aberystwyth University, ‘discovered’ in the Public Record Office (then at Chancery Lane) a series of ‘Port Books’ which recorded the customs dues charged at ports in the Elizabethan period, and also details about the ships and cargoes taxed. These Port Books were a system to ensure that customs dues were collected and sent to the Monarch’s Treasury, not embezzled by the agents in the various ports around England and Wales, nor avoided by merchants claiming that they were engaged in internal trade when they were actually exporting the goods abroad at a higher profit. Lewis transcribed the data for the Welsh ports and published it in his book in 1927. Looking at his mentions of Tewkesbury I found the names of ships, the dates and destinations of their voyages, the names of the masters of the ships, the names of the merchants and the details of the cargoes. There on the page was data about real men of Tewkesbury and their ships and activities in the 16th century. On the 19 June 1586 (two years before the Spanish Armada attacked England) the ship Peter of Teuxburye sailed from Cardiff to Tewkesbury under the command of Thomas Kylford carrying 60 bushels of bay salt for the merchant John Pleney.

Customs dues at ports had been charged by a system which began in 1254, but in 1559 the law was revised and the new system of ‘Port Books’ was created. The new system of 1559 replaced other dues traditionally charged by the Monarch, the Prince of Wales (in Welsh Ports) and the Lords Marcher. Port Books were kept from 1565 for recognised ports to record the movement of goods as part of a system to ensure that the taxes were paid. There were some exemptions such as for fish caught at sea and for corn from Ireland.

After 1559, the duty on most merchandise was “12 pence in the pound” [5%] but alien merchants (those not English citizens) were charged an extra 3d. [1p] in the pound. The duty on wine was 3 shillings [15p] per tun (‘tunnage’). [A ‘tun’ of wine was a large barrel of between 240 and 250 gallons which contained 4 ‘hogsheads’.] As you are sure to know, tax on wine and other essential items continues to this day. When a ship left a port, the merchant had to enter into a legal bond to pay the tax if the goods were exported and this was recorded in the Port Book. A document (often called a ‘cocquet’) travelled with the goods and, when they arrived at an inland port, a certificate that the goods had arrived was issued to cancel the bond. If the goods were exported then the bond ensured that the customs dues were paid.

Up until 1580, Gloucester and all the ports on the Severn were legally under the jurisdiction of the Port of Bristol but, in 1580, Elizabeth I granted Tewkesbury and Gloucester the status of being independent ports.[2] The customs officers and merchants of Bristol did not like this, as it meant that they lost revenues, and they petitioned against it. The Tewkesbury grant was eventually repealed, but that of Gloucester continued and the Gloucester Port Books survive. All the Port Books that survived, covering the period from 1565 to 1798, can be found in the National Archives[3] for all the ports of England and Wales. Of course, these administrative changes did not alter the trade itself – except in the way that taxes do – just how it was recorded. Luckily for us, the records give us an insight into trade along the Severn at this time.

The reader will have deduced that I did not know of the existence of the Port Books – but then I am not a historian. After reading about the Welsh Port Books, I discovered that Dr. David Hussey, a distinguished economic historian of the University of Wolverhampton, has worked on the Gloucester Port Books and in 2000 he published an authoritative book on them: Coastal and River Trade in Pre-Industrial England: Bristol and its Region 1680-1730.[4] It is an impressive work of scholarship. Not only that, he and his associates created a massive database of the Gloucester Port Books which is available for academic study.[5] It contains detailed records of many thousands of trading voyages on the Severn from about 1575 to 1684 with dates, destinations, the names of the ships, the names of the Masters who sailed them, the details of the goods they carried and the names of the merchants who were trading these goods.

I am glad to record my thanks to the Wolverhampton team for permission for my amateur use of it. Furthermore, the Bristol Port Books have been extensively worked on by Dr. Evan Jones, University of Bristol Department of Historical Studies, and these studies were published in 2009[6] . This database is also available for academic research,[7] although it has not been studied for this article.

The Data Relating to Tewkesbury

Tewkesbury Historical Society will be mainly interested in the Tewkesbury connection and it is clear that Tewkesbury is a place where ships once called both to deliver and to load goods. There are many ships said in the Port Books to be ‘of Tewkesbury’, which probably means that their home or usual port was Tewkesbury. Coastal trading ships, however, did not have to be registered until 1701. The Lloyd’s Registers[8] of sea-going ships date from the 1760s. Ships were ‘free-lance’, and sailed from where they delivered their last cargo to their home port. Naturally most voyages were between the biggest ports, Gloucester and Bristol, but there were some voyages by Tewkesbury ships to Haverford West and other ports in South Wales, and other voyages to Devon and Cornwall ports such as Barnstaple and Padstow. This data can tell us about the people and the goods involved in the trade on the River Severn at Tewkesbury.

The data in Dr. Hussey’s database is so large that I needed to choose a small sub-section to study: I chose to examine the data that refers specifically to ships whose home port is Tewkesbury and to a sample of the early (Elizabethan) data, which refers to goods landed or loaded at Tewkesbury. However, there is a huge amount of other data in the Port Books.

In Dr. Hussey’s database there are 1,322 voyages of ships with Tewkesbury as their ‘home port’ in the period 1575-1647. In the period 1655- 1684 there were 949 such voyages. The total number of voyages in the whole database is 8,951. Each voyage has at least 14 data items and, in addition, the full data of each cargo. Inevitably there are a number of years in which there seem to be no voyages of Tewkesbury ships; perhaps a whole Port Book or some pages are missing. In particular, the Civil War period will have disrupted trade and its recording.

Some Merchants and Ship-masters with a definite Tewkesbury connection

Listed as “merchant of Tewkesbury” were John Butler (1566); John Buller (1566); John Brown (1567); Rice Passe (1567); John Hodges (1567); Roger Turtill of Tewxbury, malt maker (1567); John Collins (1567); Edmund Welsh (1598), Richard Mayos of Turlie (Tirley, 1576). Many more are mentioned in the data. It is clear that in some cases the merchant, who was trading the goods, was also the master of the ‘trow’ that carried the goods. This is rather like the modern man who owns his own lorry or white van and provides transport services with it, carrying goods on any route for anyone who can pay. Other ships had a master who was not the merchant. These latter masters commanded a number of different ships at different times and they seem to be professional ship-masters hired for a specific voyage on a specific ship. It is not clear who owned the ships. However, ‘gentlemen’ such as “John Butler, Gentleman of Tewkesbury” (1575) and men who owned businesses such as “John Beste, Tanner of Tewkesbury” (1582), and “William Hill, Vintner of Tewkesbury” (1575), also traded barley malt. They bought malt in Tewkesbury, transported it to Bristol, Cardiff or elsewhere and sold it to a brewer thereby hoping to make a profit above the amount the trowmen had to be paid for transport. Understandably, the legal merchants of malt cargoes were often Tewkesbury maltmakers such as Roger Turtill (1567), Thomas Mallarde (1576), John Russell (1576), John Leight (1577), Richard Parkinson (1576), Thomas Dower (1576) or William Hiett (1577), each of whom was described as “maltmaker of Tewkesbury”. The data confirms a thriving trade in agricultural produce and malt from the Tewkesbury area. On the return trip to Tewkesbury, the ships brought other goods, including imports from overseas, some examples of which are given below.Cargoes

The railway occupied the concreted area.

(Tewkesbury Borough Council)Click Image

to Expand

Described here are only the goods known to have been loaded or landed at Tewkesbury. Overwhelmingly the main cargo was barley malt from Tewkesbury going elsewhere. In the three-year period 1575-1577 a total of 2,758 ‘weys’ [about 2500 tons] of malt were carried. So this means that barley was extensively grown as a cash crop locally and malted in Tewkesbury. Other important goods from Tewkesbury were wheat and peas; 288 weys [about 260 tons] were carried in the same period. Among goods traded in smaller quantities were honey and ‘metheheggleyne’ [now spelled ‘metheglin’, a Welsh alcoholic drink made from honey and flavoured with herbs, more or less the same as mead]. Interestingly mustard is not mentioned at all. In return, manufactured goods, wine from France and Spain, dried raisins and figs from the Mediterranean, soap, pitch, ‘train oil’ [oil from whale blubber used in lamps], iron and lead, and many other commodities were carried to Tewkesbury.

The size of the cargoes gives an idea of the size of the ship. As an example, “Peter of Teuxburye” in July 1586 carried 1 ton 3 cwt [1,167 kg] iron, 1 cwt [50 kg] cheese and 1 cwt [50 kg] butter from Cardiff to Gloucester. The cargoes of barley malt were measured either in Winchester bushels or more often in ‘weys’, originally a ‘cart-load’ and was equivalent to 40 bushels [volume] or just under one ton in weight. Thomas Turbill was an active trow-master and merchant of Tewkesbury at this time. On a voyage from Bristol to Tewkesbury on 12 December 1575, his ship the Martin of Tewkesbury carried 513 sugar loaves; 8 ‘piece’ [boxes?] of raisins; 9 tuns and 10 butts of sack [sweet wine from Spain]; 2 pipes [small barrels] of ‘bastard wine’ [wine from the bastardo grape variety]; 1 ton of honey; 2 tons of grain; and 2 tons of train oil. It is possible that Tewkesbury had a sweet, alcoholic and well-lit Christmas in 1575! The largest cargo of malt observed at this period was 18 weys [a little under 17 tons]. This was carried from Gloucester to Bristol by the ‘Morgans’ of Tewkesbury, under her master Thomas Turbill, who was also the merchant, sailing on the 9 July 1576 from Tewkesbury to Bristol. More typical was that on the 11 October 1576, the John of Tewkesbury sailed for Bristol under the master John Shalle or Shawe carrying 14 weys of malt from Tewkesbury for the merchant Thomas Mallarde, malt maker of Tewkesbury. Thus it can be seen that the Port Books contain fascinating details of commerce to and from Tewkesbury in this period.

Malting of Barley

aptly named ‘Maltings’, a retirement

complex designed to recall

the former building [Editor] Click Image

to Expand

Tewkesbury was an important centre for producing and exporting grain and malt from the 13th century at least.[9] The Port Book data confirms that malting was an important industry in Tewkesbury in Elizabethan times and it continued on into the middle of the 20th century. I can remember visiting the ‘Maltings’ in Station Street, Tewkesbury, with my father Rufus in the late 1940s. We were shown the building on the south side of Station Street, next to the engine shed. It consisted of many floors of warm, very low-ceilinged malting chambers whose floors were covered with barley being ‘malted’. What I saw was analysed by my fledgling scientist’s brain; I asked questions and looked things up afterwards.

The barley was spread in layers a few inches thick and then watered with hoses. The heat came from fires below and was distributed through brick ducts not unlike a Roman ‘hypocaust’. In the dark, damp warmth the barley seeds sprouted and developed the crucial enzymes, which turned the starch of the barley kernel into simpler sugars. Men had to rake and turn the barley to ensure even malting. Then the temperature was raised and the barley was turned again and dried out. It now had more flavour and it contained sugars. The brewer would ‘mash’ the malt in hot water that, after cooling, could be fermented by added yeast and so turned to alcohol. This became ale or, if flavoured with hop flowers, it became beer. (Nowadays the two terms ale and beer overlap.) It was the dried malted barley that was shipped off to the brewers. Some of the barley malt was raised to a higher temperature, ‘roasted’ to give it more flavour and colour. I remember that it was very tasty to chew. The raw barley was raised in hessian sacks on a pulley but it was spread over the malting floor by men with shovels. They also turned the malt and shovelled the finished malt into hoppers so that it could be weighed into big bags on the floor below. It was hot, hard work. The bags of malt will then have been carried in carts down to the Quay to be loaded on the ‘trow’.

Apart from being transported by railway, the process itself has not changed for centuries. The modern malting process is the same but it is automated, mechanised and scientifically controlled, and transport of the finished malt is no longer by trows on the Severn. There was a major trade in malt because of the large amounts of beer drunk by great cities, such as Bristol. Beer is still drunk but now is made worldwide. Today, British barley malt is exported to over 80 countries.[10]

Evidence for Spellings of Tewkesbury

There were many spellings in the original Port Books. The Welsh include Teuxbery, Teuxberie, Teuxberye, Teuxbury, Tewexbury (they have been standardised in the Wolverhampton University database so it does not bear on this question). No doubt each port officer had his own spelling, but the sound of it in Elizabethan times emerges. It begins with a single complex syllable beginning with a T-sound (not a ch-sound) and ending with an X-sound which is then followed by ‘bury’ or ‘berry’. So it was probably pronounced Tew-xberry not Chew-x-bury.

Conclusions

As a boy in Tewkesbury, I visited the Maltings and I saw malt being made. I did realise that being next to the railway line was important and that was how barley and malt were transported then. I can now look at Tewkesbury Quay and the old etchings and paintings of Severn sailing trows in a new way. I can visualise the cargoes of malt being transported in sailing trows century after century. I can see men with known names sailing specific ships on known dates to known destinations and I know the details of their cargoes. I know some of the names of the merchants and I know something about the more exotic goods that were brought back to Tewkesbury on the return voyage.

Because the labours of the modern historians have created databases, it may be possible to connect up local data on individual merchants, malt-makers and trowmen with the data on the shipping trade that helped create their wealth. It is now easy to search for a specific name (you do have to allow for variant spellings) or all cargoes of a particular sort. The whole excitement of local history lies, I think, in this deepening of our understanding of how things really were in the past in the places we love. Economic statistics are interesting but the individual human connections with real people are exciting.

References

- The Welsh Port Books (1550-1603) with an analysis of the customs revenue accounts of Wales for the same period, by Edward Arthur Lewis, London 1927, issued by the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (xivii).

- J. Bennett, History of Tewkesbury, 1830 pp 43-44. This is now available as a facsimile edition by print-on-demand. Originals are sometimes available for sale at a price between £150 and £200. A free e-book is available online on Google Books.

- National Archives [NA], reference E 190.

- David Hussey, Coastal and River Trade in Pre-Industrial England: Bristol and its Region 1680-1730 (Regatta Press, New York, 2000). This book is still in print.

- Information about the Wolverhampton University database of Gloucester Port Books:

- S. Flavin & E. Jones (editors), Bristol’s Trade with Ireland and the Continent, 1503-1601, Four Courts Press (2009).

- Bristol Port Books database of Bristol University.

- Lloyd’s is a 17th century insurance market and its first Register was published in 1764 in order to give both underwriters and merchants an idea of the condition of the vessels they insured. [Editor from Wikipedia]

- British History On-line: Tewkesbury Economic History

- See the website of The Maltster's Association of Great Britain. There is a good deal of useful information such as that at here.

![In 2015 the site is occupied by the<br>aptly named ‘Maltings’, a retirement<br>complex designed to recall<br>the former building [Editor]](/images/THS07531.jpg)

Comments